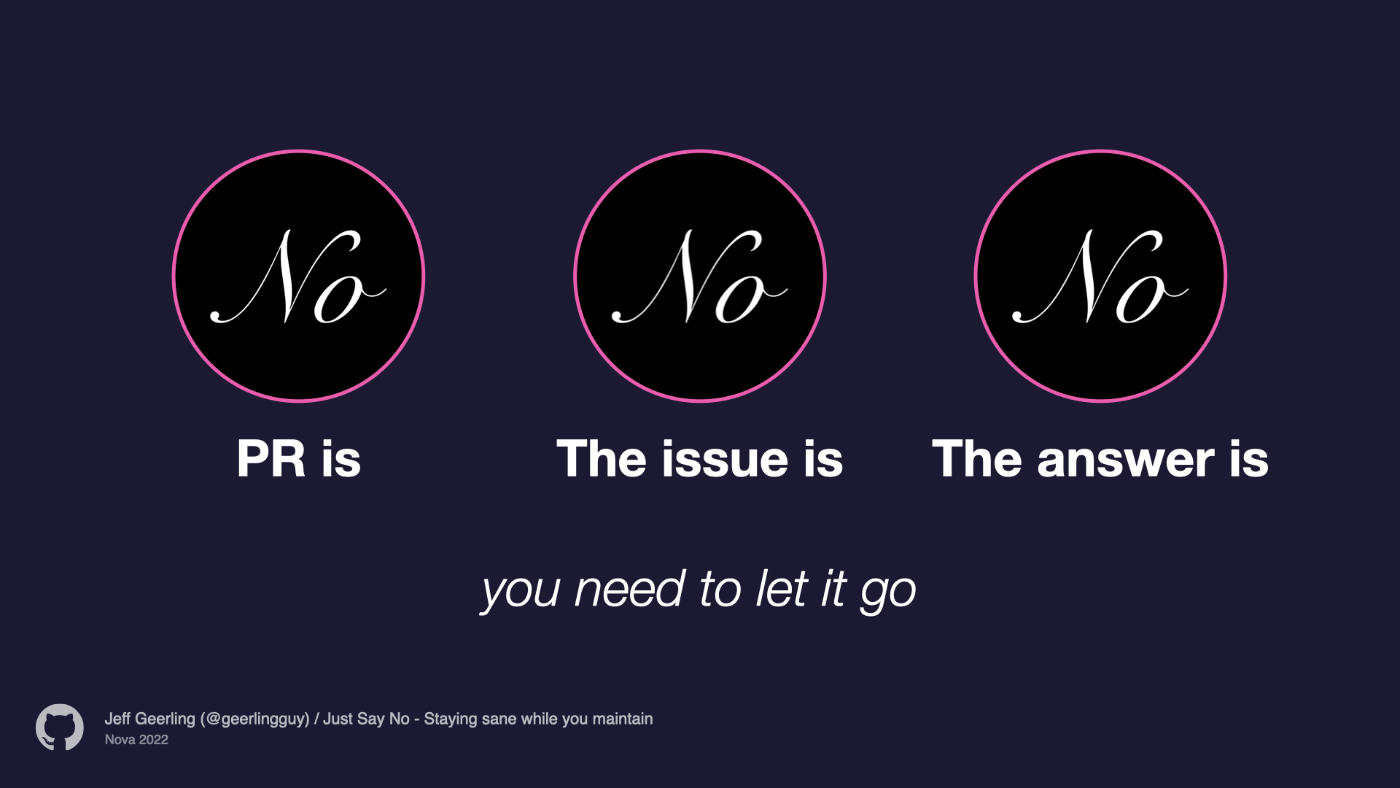

Just Say No

Saying yes is easy—at first.

It makes you feel better. And it makes you feel like you can do anything! And the person you're saying yes to also gets a happy feeling because you're going to do something for them.

Saying no is hard. It's an admission you can't do something. And worse still, you're disappointing someone else who wants you to say yes.

But here's the thing: none of us is a god. We're people. We have a certain amount of mental resources.

Some people are kind of crazy and can do a lot more than you or I can, but nobody can do it all. And sometimes you can burn the midnight candle for a little while, but you're just building up debt. Every 'Yes' is a loan you have to pay off.